Older than the Rothschilds, more versatile than the Barings or the Hambros, Europe’s Warburg-family banking dynasty has prospered ever since it started changing money in 1559. Along with bankrolling potentates and private tycoons, the Warburg family has bred many of its own philanthropists, scientists and scholars. In 20th century Germany, members of the family or their partners were friends to Kaiser Wilhelm, represented their country at Versailles (and refused to sign the treaty), sat on 100 corporate boards. After Hitler came in, the Warburgs—being Jews —were forced out. Now, however, the resilient Warburgs are returning with a rush.

[TIME April 29, 1966 ]

In Germany, Eric Warburg, 66, a naturalized U.S. citizen, has helped make his family’s Hamburg investment bank one of the fastest-growing financial houses on the Continent. His cousin Siegmund Warburg, 63, has become the most rapidly expanding merchant banker of London’s City. Increasingly, the two men are uniting. Siegmund holds an interest in Eric’s Hamburg bank, and Eric has a stake in Siegmund’s recently started Frankfurt branch.

One Desire. Though they are disparate personalities—Eric is athletic and uncomplicated, Siegmund is intellectual and rather mysterious—the two have much in common. Both specialize in international finance, and both have shaken encrusted bankers by putting their trust in modern methods and young associates. And both are driven by a desire: restore all the past glory to a many-faceted clan, whose current members range from Berlin’s Otto Warburg, a Nobel-prizewinning biochemist, to Connecticut’s Economist-Author James Warburg (The West in Crisis).

Eric Warburg in 1944 went back to Germany in unusual style; an Air Force officer, he was the chief U.S. interrogator of Hermann Göring. He also persuaded the Allies to let his family firm quickly resume operations, then left it in the hands of associates to whom the family had entrusted it in 1938. It still carries their names, Brinckmann, Wirtz & Co. In 1956 he returned full time, now shares authority with the Brinckmanns and other partners but the Warburgs own the largest share of the business. (Eric also owns a substantial part of the Wall Street investment-banking firm that he founded, E. M. Warburg & Co.) By making faster decisions than bigger, bureaucratic German banks were able to, Warburg rebuilt a substantial business in international underwriting and financing foreign trade. Today bankers throughout Europe send their bright young men to train at Brinckmann, Wirtz, and members of the firm are directors of two dozen German corporations.

Sober Nightclub. Even more influential is London’s Siegmund Warburg. He fled to Britain with less than $25,000 in 1933, later stormed the City’s tight inner circle by investing in growing companies, reorganizing sick ones and exploiting his best asset: savvy in world finance. As a master strategist of Reynolds Metals’ 1958 battle for control of British Aluminium, Warburg fought most of the British banking Establishment—and won. His S. G. Warburg & Co. also plotted most of the press takeovers by both Lord Thomson and Cecil King, helped Chrysler buy into Rootes Motors, arranged financing for Italy’s autostrada, managed the first U.S. corporate bond issue in Europe, for Socony Mobil last year.

Prime Minister Wilson, an admirer of Warburg’s modernizing influence in British banking, has taken Siegmund in as a close adviser. Warburg has shaken up what he calls the City’s “ingenious sloppiness” by introducing Germanic organization and discipline; he even plots the seating at his business lunches with military precision. His officers often work so late that competitors call Warburg’s bank “the nightclub.” Secretaries transcribe every important meeting in the place, rush out a daily precis to all the directors—many of them trekking about the world on business. For his tight ship, Warburg has recruited a highly diverse and individualistic crew, including former Reuters Correspondent Ian Fraser, former Ambassador to France Lord Gladwyn and former KLM President E. H. van der Beugel.

Yet in his ambition to reassert the dynasty, Siegmund Warburg faces a frustration. His only son left the firm to start his own accounting business, and the two men are not close. The War burg future seems to depend on the smaller branch in Germany, where Eric Warburg is carefully bringing along his 18-year-old son, also an American.

THE WARBURGS: THE 20TH CENTURY ODYSSEY OF A REMARKABLE JEWISH FAMILY

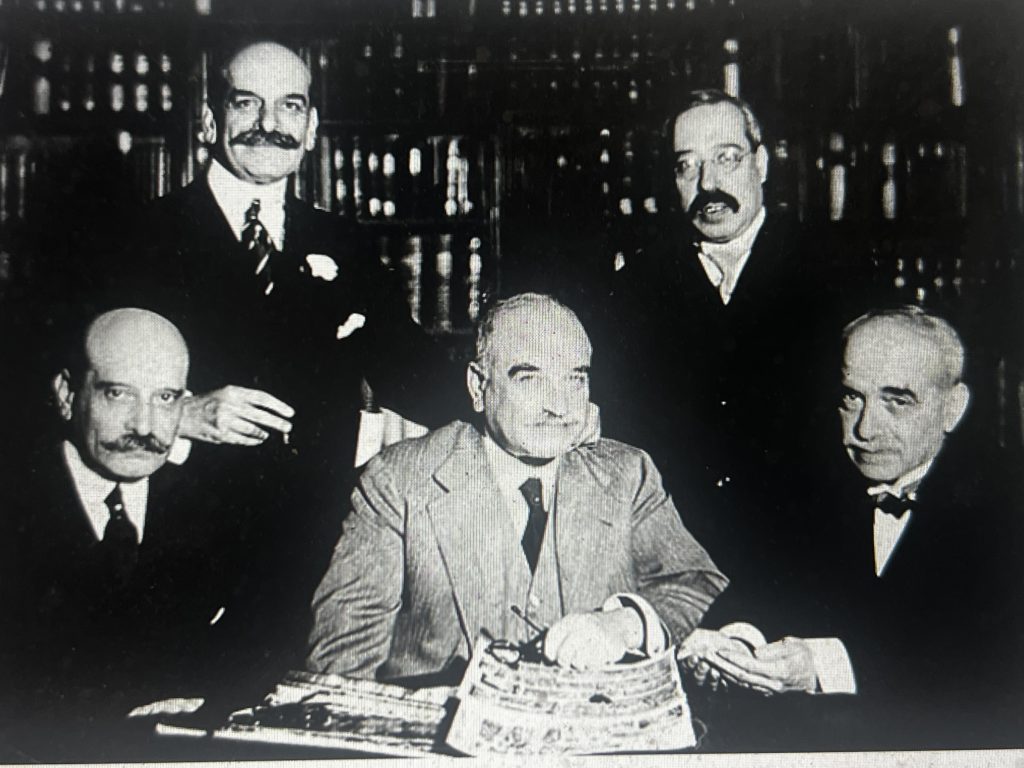

From left to right> Paul, Felix, Max, Fritz and Aby

By Ron Chernow

The Warburgs appear in the sixteenth century as “Court Jews” in the town between Frankfurt and Hamburg from which they got their name – not being allowed, by German law at the time, to have surnames of their own. Forbidden also to own land or carry on everyday trades, the trade of the Jews became the handling of money, as lenders at interest and dealers in foreign exchange. Georg Simmel said that the Jews provided “the best example of the correlation between . . . money interests and social deprivation.” Money, in Simmel’s view, was the one thing that could make up for the stigma inflicted on the Jews; and money was the one trade that Christian society would let them pursue, thanks to the Church’s mistrust of interest and the aristocracy’s mistrust of anything not a tangible product of the soil. The Jews were thus concentrated in a role that made them alien, resented – and indispensable; and in the most dynamic and mysterious sector of the modern economy, finance. This was a dangerous niche to occupy, though not more dangerous in the German principalities, as yet, than anywhere else.

When Warburgs moved into Hamburg in the seventeenth century and set up as international bankers they became doubly marginal. The problem for traders was always whether you could trust their foreign counterpart; only Jews, not having a real country of their own, could reliably do business with their co-religionists across national boundaries. Their exclusion from the mainstream made them ideal go-betweens, with a global view of the opportunities arising as Germany unified itself, and Hamburg became its principal port.

M.W. Warburg & Co. thrived as a private bank, deeply involved both in trade and in the German industrial revolution. It was a family concern in every sense. When more capital was needed, young Warburg men were married into other wealthy Jewish families, who gave dowries with their daughters. These marriages also created commercial ties between Hamburg and Russia, Hungary, France. The bank still had two long-term problems: new capital could not be raised in a predictable way, and sons were not always as good at business as their fathers. Thomas Mann was the archetypal son of a mercantile family who preferred culture to commerce; his Warburg counterpart (and contemporary) was Aby M. Warburg, who became a great art-historian and bibliophile – lavishly subsidised by his brothers, who stuck to their last in the bank. Money and art did not have to be enemies, of course. The Warburgs, along with Jim Loeb (who married a Warburg), endowed such distinguished cultural institutions as the Loeb Classical Library, the Warburg Library (moved to London in 1933), the Juilliard School, and the Art History Department of New York University.

By 1914 M.M. Warburg was the leading German commercial bank, and the family was also well established on Wall Street. Felix M. Warburg and his brother Paul both married into Kuhn, Loeb and settled in New York. Paul, a brilliant monetary theorist, masterminded the belated foundation of an American central bank, the Federal Reserve, in 1913. The American Warburgs did not establish a major financial business in their own name, but they were successful enough to become leading philanthropists, patrons of the arts, and political advisers. They blended securely into the American establishment, unlike their German cousins. But it is the more extreme and tragic German family history that gives Chernow the structure, and the moral, for his book.

The German Reich of 1871 enfranchised the Jews. Some disabilities remained – they could not be officers in the army, for example – but for the first time they could consider themselves citizens of Germany. Chernow views their emancipation as a tainted gift: “Discrimination had acted as a preservative to their identity, while freedom threatened to corrode their unity and dilute their culture. Henceforth, they would try to be both Jewish and German at once – with initially happy but ultimately tragic results.” The Warburgs indeed threw their hearts into becoming “truly German,” from heel-clicking military service to Max Warburg’s enthusiastic support of German economic imperialism before 1914. A hundred thousand German Jews served in the war, out of 550,000 in all. By 1932 the rate of intermarriage by German Jews had reached sixty percent, and their cultural achievements made them the most creative minority of modern times.

When things went so terribly wrong in 1933, the Warburgs took the stand that they were as good Germans as anyone else, and would fight to remain in their homeland. As late as 1937 Max Warburg proposed, as the toast to a bar-mitzvah boy, “Always remember you are a German.” Meanwhile the bank was being “Aryanised” by slices, and much of its day to day business came to be helping German Jews liquidate and move abroad. Max himself did not sail for New York until August 1938.

Throughout the twenties and thirties the Warburgs had carried on a running battle within their own community, with the Zionists. In 1930, Chernow notes, “several hundred Jewish leaders signed an ad asserting their German loyalty and rejecting a Jewish homeland.” The Warburgs supported Jewish settlements in Palestine, but told Chaim Weizmann that most Jews still wanted to be accepted as full citizens in the West. They refused to confine their aid for Jews in distress to those wanting to move to Palestine, and infuriated the Zionists by financing agricultural settlements for Jews in Russia and the Ukraine during the 1920s. Above all, Felix M. and other Warburgs opposed a Jewish state in Palestine. They hoped for peaceful coexistence between Arabs and Jews, and believed that Zionist policies made it inevitable that the two peoples would eventually go to war.

Chernow – with benefit of hindsight – considers the stance of the Warburgs and the elite of German Jews to be profoundly misguided. “The Warburgs struggled,” he writes, “with an insoluble identity crisis, trying to solve the riddle of who they were. . . . The Nazis would exploit the identity conflict among German Jews, which weakened their capacity to withstand assault.” This critique of the assimilated German Jews recurs regularly throughout Chernow’s book, and provides its closing words: “Was the germ of anti-Semitism finally dead in Germany? Or was it only dormant and waiting to flare up again? Had the Warburgs come back [to Hamburg] in vain?”

The underlying narrative of The Warburgs is of a twentieth-century Exodus. The German Jews enjoyed their flesh-pots, not believing that a hostile Pharaoh would rise up to oppress them. God sent them into the wilderness to reclaim their true identity; but even there they worshipped the golden calf. They lay with “the daughters of Moab. . . . and bowed down to their gods” (Num. 25: 1-2). God requites them with slaughter and plague, until they return to the strait way.

This is the cautionary tale that haunts Chernow’s “family saga,” a narrative that applies both to individual Warburgs who dilute their Judaism and take gentile wives, and to the German Jews collectively. To have a “real” identity you must remain an observant Jew, marry within the faith, and be a Zionist. But in post-war America the Warburgs continued their German ways, moving away from Judaism “as the doubts of one generation hardened into denial in the next.” Chernow argues that their successful acculturation came “at the expense of their religious identity”; they took up “the pursuit of pleasure that comes to dominate many rich families,” and they discarded Judaism because it was “a barrier to social advancement, an unwanted burden from a darker past.”

In 1959 Jimmy Warburg went to Temple Mishkan Israel, in Hamden, Connecticut, and denounced Israel for creating “a new chauvinistic nationalism”; he called it “a state based in part on medieval theocratic bigotry and in part upon the Nazi-exploited myth of the existence of a Jewish race.” Sir Siegmund Warburg, in turn, became a bitter critic of the Likud regime that came to power in 1977 – an example, for Chernow, of his “headstrong, unpredictable nature” and his tendency “to dismiss Zionism as another brand of nationalism.” But the Warburgs, and others like them, had long held a consistent position. They wanted Jews to be “normalised” as a minority within Western democracies rather than as a majority in a newly-created Jewish state; and they believed that Jews had to choose one path or the other to emancipation. As the financier Jacob Schiff put it, “I cannot for a moment concede that one can be at the same time a true American and an honest adherent of the Zionist movement.”

Chernow’s tale of apostasy and retribution is only one version of the Warburg saga. No Warburgs renounced their Jewish identity in the 1930s, though they believed and hoped – perhaps for too long – that they could remain Jewish citizens of Germany. Hitler’s decision to implement the Holocaust in 1941 had nothing to do with the choice of individual Jews to have more or less of “Jewish identity.” The concept itself, as Chernow uses it, rests on ideas of purity and defilement that conflict with the modern reality of constant assimilation, emigration, transculturalism, and hybridisation. It is well known that the more assimilated European Jews were, the more chance they had of escaping the Holocaust: it was easier for them to emigrate, and they had more potential helpers in gentile society. More than two-thirds of the German Jews survived, including almost all the Warburgs; Jews who lived through the war in Germany were mainly married to Christians or had a gentile parent. If God was punishing the Jews for backsliding, why did he allow the assimilated to escape and the Orthodox to die?

Jews like Max Warburg supported German imperialism because they considered themselves German, just as many American Jews adopted a chest-thumping Americanism during the Cold War. Nonetheless, what remains most impressive about the Warburgs is not their nationalism but their internationalism (though when Max Warburg writes in favour of world federalism Chernow calls him “a dreamy old man taking refuge in simplistic visions.”) Economic internationalism also fuelled the great Warburg success story after the war, the rise of S.G. Warburg & Co. in London.

Sir Siegmund Warburg’s invention of the Eurobond market in the early 1960s was a natural offshoot of the family tradition. During the German inflation of the twenties, young Siegmund had seen the family bank circulate foreign currencies in Germany as a substitute for the crumbling mark. Eurobonds assembled short-term dollar deposits in Europe for long-term investment lending across national boundaries; the first issue was regulated by British law, signed in Holland, traded in Luxembourg, denominated in dollars, and for an Italian borrower. As Jacques Attali puts it in his book on Siegmund, Eurobonds made S.G. Warburg into “the symbol of the new form of post-war world capitalism: totally delocalized.”

Chernow dismisses Attali’s book as untrustworthy; his own volume is authorised and rests on a solid base of family documents and interviews. But Chernow is always trying to cut Siegmund down to size, in contrast to Attali’s hero-worship (it is easy to see who Attali took as a model for his own ambitions as a financial titan). This difference of attitude to Siegmund reflects the concerns of the two biographies. Chernow focuses on family relations; he gives the powerful Warburg women their fair share of the limelight, if he also includes too many pages of domestic trivia. He supplies a lively and dramatic account of family ups and downs, but says curiously little about events at the office‹how the family banks were run, how much money they made and how they made it, what special role they played in modern financial systems. Chernow gives no figures on how rich individual Warburgs were, or where their wealth is placed today.

Attali handles public issues with much more detail and insight than Chernow, while drawing a veil over private life; he tells you only that Siegmund had “adventures,” whereas Chernow describes his affair with the ballerina Danilova (and Lola Hahn-Warburg’s with Chaim Weizmann too). But the deep difference between the two books is in their philosophies. For Chernow, the assimilation and dispersal of the Warburgs represents a failure to enter the promised land; for Attali the Warburgs were “uncommon seers, escaping, thanks to their centuries-old universality, from the general tragedy.”

After Siegmund’s death in 1982, S.G. Warburg outgrew its family roots. It has become vastly larger and more diversified (Siegmund always feared bigness for its own sake), its stock is publicly traded, and Siegmund’s successor is a gentile outsider, Sir David Scholey. In England, the U.S. and Germany, the distinctive Warburg contribution has been absorbed into the broader financial cultures. Institutions that the Warburgs had a hand in creating now are collective rather than individual, corporate rather than familial, of the mainstream rather than specifically Jewish. Chernow gives an essentially suspicious account of this gradual dilution of the Warburg “identity,” since the arrival of the Jew known only as “Simon of Cassel” at Warburg in 1559; though he must concede that only the re-awakening of archaic anti-semitism could now give that identity back.