Coming from humble roots in the official ghetto for Jews in Frankfurt (now in Germany), the Rothschilds became a European banking dynasty that helped develop international finance as we know it, leaving an enduring impact on global politics, industry, and philanthropy.

Given the family’s power and prominence, they have for centuries been the target of virulent antisemitic conspiracy theories that helped fuel some of the worst moments in European history. Despite this persistent bigotry, the real history of the Rothschilds reveals a remarkable story of the transformation of European banking. Their true legacy lies in the establishment of enduring institutions that helped shape the modern financial world.

By Adam Hayes|investopedia.com

Updated April 25, 2025

Fact checked by Suzanne Kvilhaug

Key Takeaways

- The Rothschilds created the first international banking network through five brothers across key European cities.

- Together, they pioneered cross-border finance, often having clients on both sides of enemy lines during the many intra-European wars of the 19th century.

- The Rothschilds adapted to the Industrial Revolution through key railway and infrastructure investments.

- Today, the Rothschild name is a virtual synonym for wealth and societal influence.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/dotdash-history-rothschild-family-FINAL-71ea8f9db9ff4225801445367ce20efb.jpg)

Origins and Early History

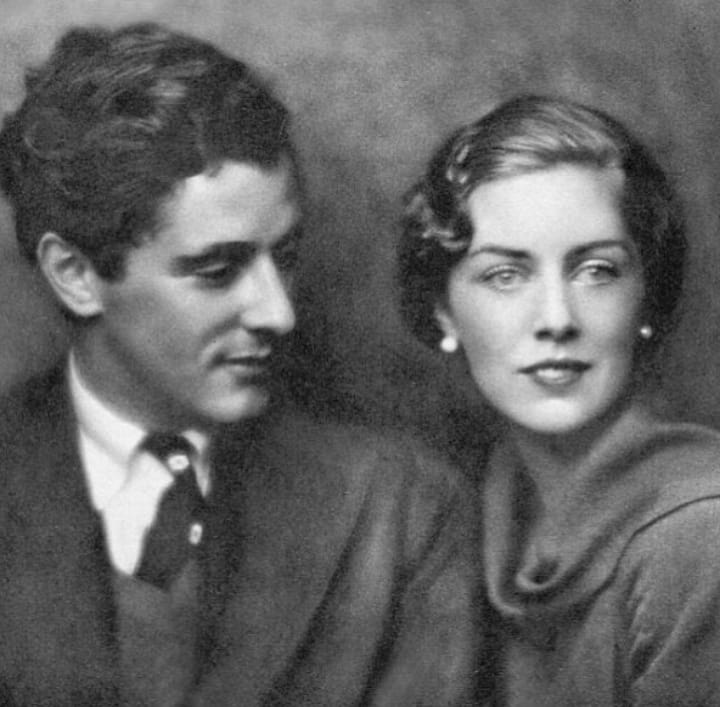

Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744–1812) was born into modest circumstances in Frankfurt’s Jewish quarter. With its repressive laws and crowded conditions, the quarter was an unlikely birthplace for a financial empire. Yet, it was precisely these constraints that helped forge the Rothschild approach to banking.

As a young man working as a coin sorter and currency exchanger, he came into contact with wealthy collectors, including members of the Prussian nobility, and he developed a sophisticated understanding of international trade and credit operations.

He and his wife, Gutele, had 10 children in the late 1700s. Of those children, five sons would branch out across Europe and establish the Rothschild fortune.

Expansion Across Europe

Five of Mayer’s sons received intensive training in languages, mathematics, and business, but also specialized knowledge suited for following him into the family business. Here are the five, along with where they emigrated to:

- Nathan (1777-1836), London: He gained the most wealth initially, establishing N.M. Rothschild & Sons, which would play a pivotal role in financing British government projects.

- James (Jakob) (1792-1868), Paris: Founded de Rothschild Frères, which James used as a base to integrate into French high society.

- Salomon (1774-1855), Vienna: Salomon’s move gave the family a strong presence in Eastern Europe, where he became a trusted financier for the Habsburg court.

- Karl (1788-1855), Naples: He founded the Italian branch of the Rothschilds, which would become influential in regional finance and later winemaking.

- Amschel Mayer (1773-1855), Frankfurt: The eldest managed the Frankfurt business, ensuring continuity with the family’s origins.

This geographical dispersion enabled the family to bridge distinct financial markets, laying the foundation for one of the first multinational banking enterprises.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Clipboard01-019ae9e1facf4e30ac7c0f68cc5776bc.png)

Rise to Influence During the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803 to 1815) provided the family’s first major opportunity. The brothers developed a sophisticated system of credit notes and bills of exchange that allowed transfers of funds without moving physical coins. If Britain needed to pay troops in Austria, the Vienna branch would pay in local currency while London collected from the British government. This system was faster and safer than previous alternatives.

The family also arranged significant wartime loans, including £5 million to Prussia in 1818 (about $675 million in 2025 dollars) and another £9.8 million to Britain’s allies during postwar restructuring.

Events during this time would later be fastened onto by antisemitic pamphleteers. Researchers have traced the first widespread conspiracy theory about the family to a widely disseminated 1846 political pamphlet. It famously claimed the Rothschilds made their fortune when Nathan Rothschild rushed ahead of news of Napoleon’s loss at Waterloo to trade off the emperor’s fall before others found out. Far less dramatically, but more importantly for what did occur, he helped raise the funds for the British troops that helped end Napoleon’s hold over much of Europe.

These connections, as well as profitable investments, earned the Rothschilds widespread recognition from European rulers, cementing their reputation as indispensable bankers capable of managing enormous sums during crises—of which there would be many to come.

Influence During the Industrial Revolution

As Europe transitioned after the war, the Rothschilds shifted their focus to profit from the burgeoning private industrial economy. Their banking operations financed critical infrastructure projects—including railways, mines, and factories—that drove economic transformation across the continent.

By funding railway construction across several European countries, the Rothschilds helped to integrate disparate markets and stimulate commerce and growth. The Rothschilds often managed and coordinated major infrastructure projects, for example, by helping to standardize railway gauges.

Their financial reach extended to the mining and energy sectors. Investments in the early oil industry, coal, iron, and copper not only yielded substantial returns but also supplied the raw materials needed for industrial production.

Important

The Rothschild family had been involved in major philanthropic projects since its early days. That included supporting initiatives to advance the welfare of the Jewish community in Europe, which was subject to persistent and often violent antisemitism. Over time, members of the family championed Jewish emancipation and played influential roles in the early Zionist movement, helping to fund the establishment of settlements in Ottoman- and then British-controlled Palestine, the foundation of modern-day Israel.

Challenges and Adaptation in the 19th Century

In the 19th century, the rise of joint-stock banks and large corporate institutions began to challenge the traditional family-run banking model. New forms of industrial financing and the emergence of public stock exchanges meant the Rothschilds needed to adapt their practices while maintaining their reputation for stability and discretion.

Political upheavals across Europe also tested the family. The revolutions of 1848 that swept across much of Europe threatened the aristocratic powers that had long been the foundation of the Rothschilds’ business relationships. The unification of Germany in 1871 and the subsequent shift in European power required careful diplomatic and financial maneuvering to maintain their influence.

In response to these challenges, the Rothschilds diversified their investments beyond government bonds into industrial ventures, particularly railways and mining operations. The family also formed strategic alliances with other banking houses and maintained close relationships with key political figures across Europe.

Throughout these transitions, the Rothschilds continued to face persistent antisemitic attacks and discrimination. However, their response was to further entrench themselves in European society through philanthropic works and cultural patronage, while maintaining their commitment to Jewish causes and community support.

Tip

The Vichy government in France expropriated Rothschild’s Bordeaux properties during World War II, while the Nazis confiscated valuable art and other precious objects from the Austrian branch (a portion of these were returned by the Austrian government in 1998).

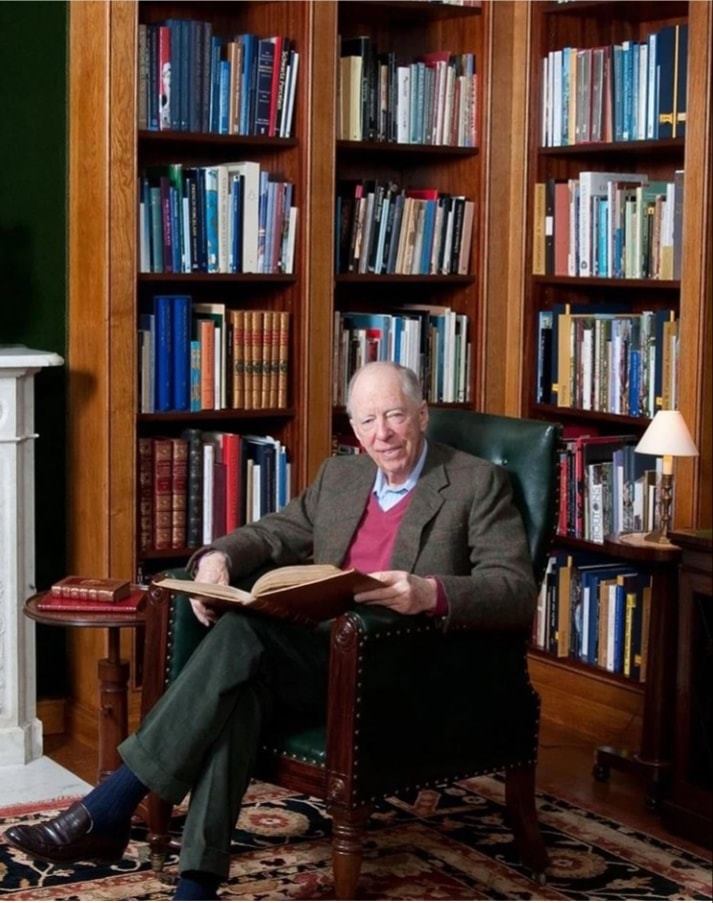

The Modern Era

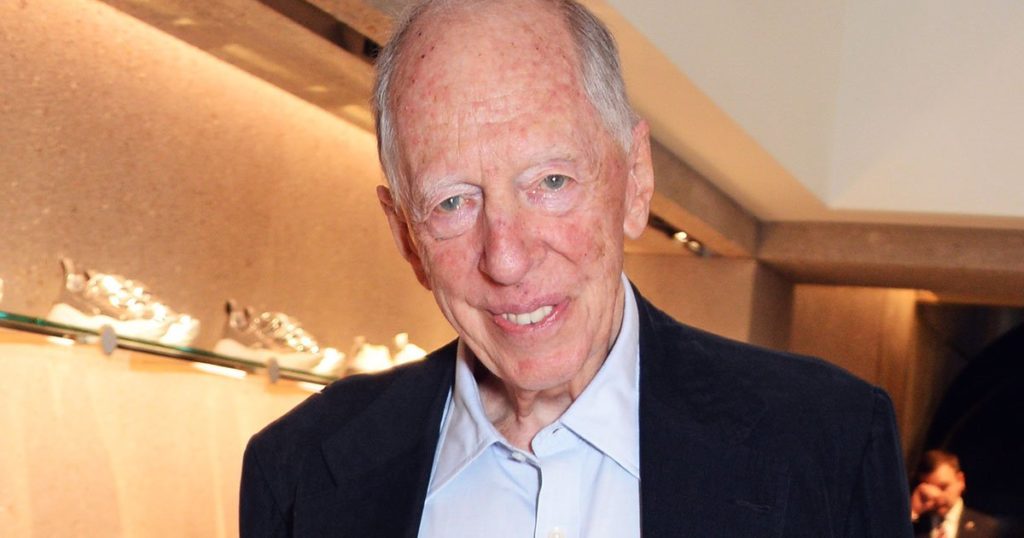

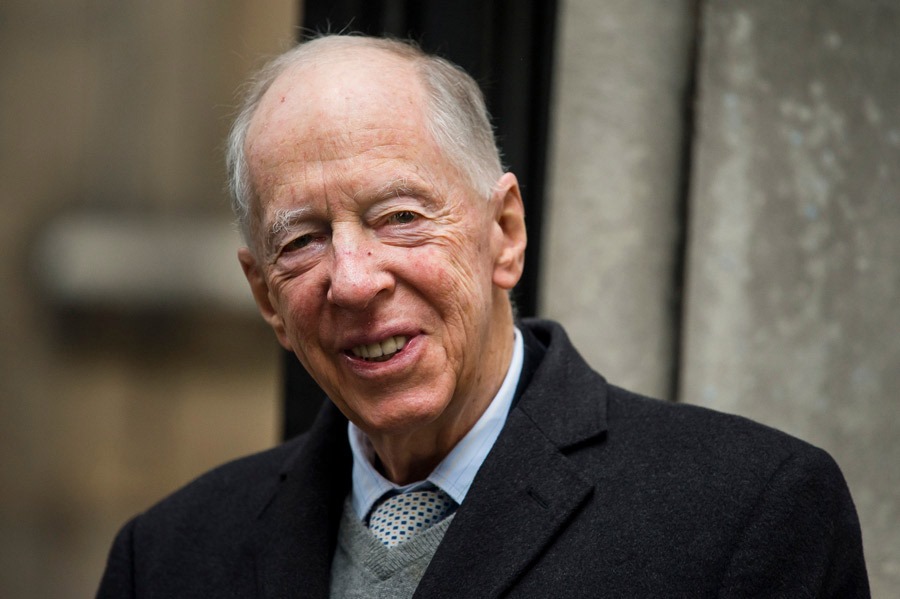

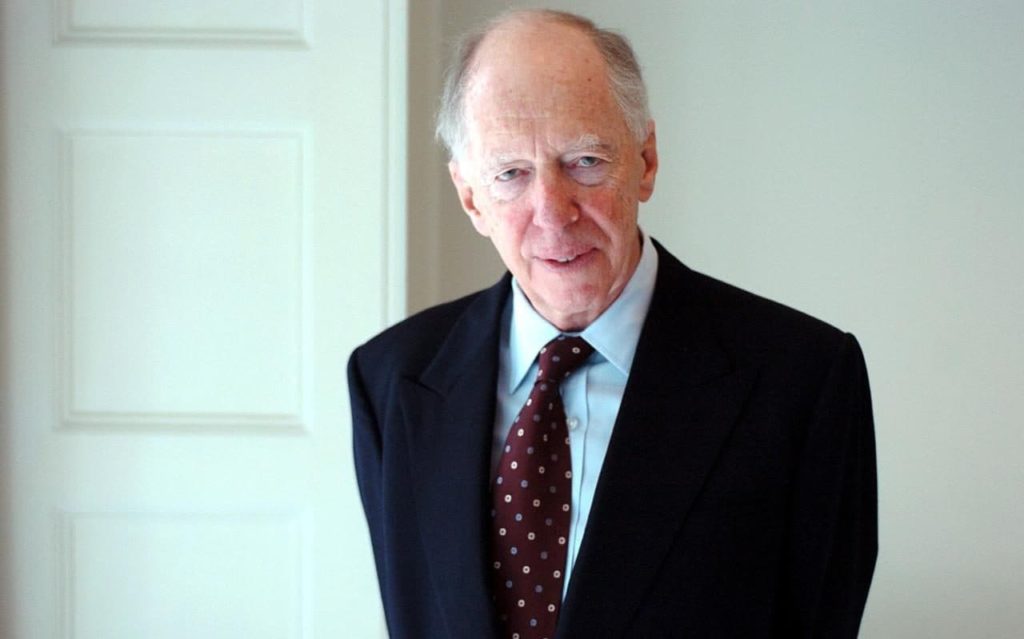

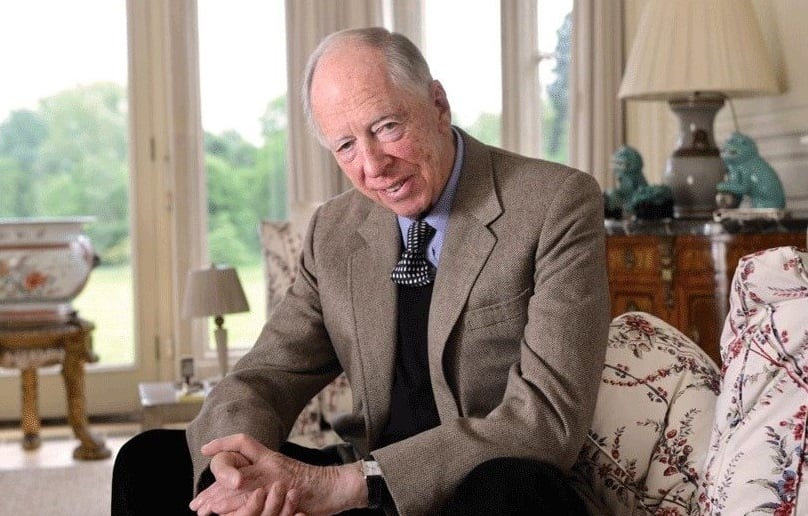

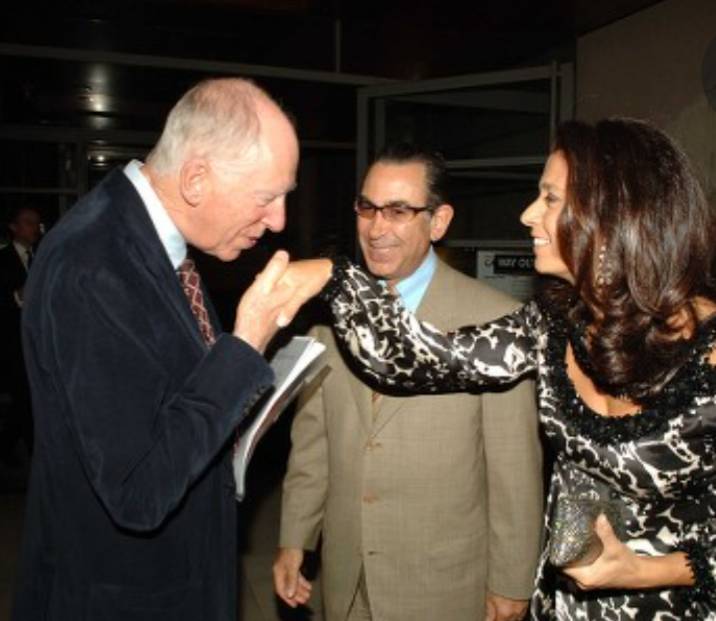

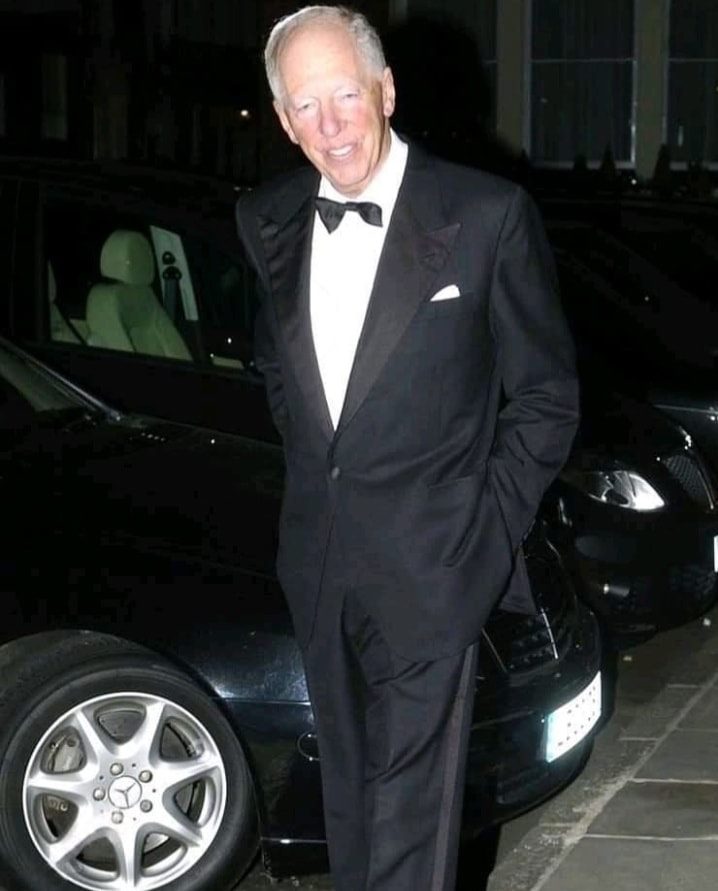

Mandatory Credit: Photo by Shutterstock (9938635bg)

Ambassador Mark Regev, Sir Trevor Chinn, Lord Jacob Rothschild and Tony Blair.

Herzog Centenary, London, UK – 18 Oct 2018

Mandatory Credit: Photo by Shutterstock (9938635bd)

Sir Trevor Chinn, Lord Jacob Rothschild and Tony Blair.

Herzog Centenary, London, UK – 18 Oct 2018

Mayer Amschel, the founding father of the Rothschilds, once warned his sons “that Jewish fortunes as a rule don’t keep longer than two generations.” While the Rothschilds would prove an exception, the various family rivalries, succession dramas, and split inheritances would do much to dilute the great fortune the family once had.

Nevertheless, the Rothschild holdings span many industries, including financial services, real estate, mining, energy, and agriculture. The family also owns more than a dozen wineries throughout the world.

The Rothschild name continues to carry significant weight in international finance, though the nature of their influence has evolved. Two world wars, political shifts, and economic transformations forced the family to reconfigure its business strategies. After World War II, the family’s banking operations were reorganized to address the new global economic order.

Modern Rothschild businesses focus mainly on merchant banking, wealth management, and financial advisory services, adapting to contemporary financial markets while maintaining their tradition of excellence and discretion.

In Britain, N.M. Rothschild & Sons evolved from a traditional private bank into a modern investment firm with a significant advisory role in mergers and acquisitions. While the Rothschild’s bank in France was nationalized in the 1980s, it has been reconstituted under new management, paving the way for creating Rothschild & Cie Banque.

In 2003, the merger of the British and French operations consolidated the family’s interests into a single global brand, Rothschild & Co., still a major financial advisory firm with a diversified portfolio spanning investment banking, asset management, and private banking.

Tip

The Rothschild family crest contains the motto Concordia, Integritas, Industria—Latin for harmony, integrity, and industriousness.

The Bottom Line

The Rothschild family pioneered international banking practices that we often take for granted today—from sophisticated credit instruments to cross-border financial networks. Their conservative approach to risk and ability to work across political boundaries created a template for modern global banking. While their story has often been distorted by dark antisemitic conspiracy theories, their contributions to worldwide finance and the rise of modern capitalism are essential parts of modern economic history.

>

The origins of the name ‘Rothschild’

The family take their name from the house they occupied in the Judengasse in Frankfurt; pictorial representations of names were engraved or painted onto keystones and doors, and people often retained their names, and emblems, when they moved to another house.

The name can be traced back to a sixteenth-century ancestor of Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744-1812), Isaak Elchanan, who took the name Rothschild from a small house he occupied at the southern end of the Judengasse called zum Roten Schild (‘House at the Red Shield’). The practice of using surnames was well established in Germany by the 1500s, and when his grandson, Naftali Hirz moved to the Hinterpfann (a tenement in the back of a house at the northern end of the Judengasse) in 1664, he took the name Rothschild with him. Frankfurt Jews were officially required to adopt surnames by the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt in 1807. Such laws were passed in order to improve the governability and taxability of the Jewish population.

By the early 18th century there were ten or twelve Rothschild families in Frankfurt. Mayer Amschel Rothschild was born in the Hinterpfann in 1744. He lived here throughout his childhood and much of his married life, until, in 1784, together with his wife Gutle and their first five children, he was able to buy a larger house in the Judengasse; this property was known as the ‘House at the Green Shield’. It was here that Mayer and Gutle’s ten children grew up, their five sons to become the future bankers to European monarchs and governments.

The Rothschild Coat of Arms

The five sons of Mayer Amschel Rothschild were placed on the first rung of the nobility by the Austrian Emperor in 1817. They were granted the right to armorial bearings, and to use the suffix ‘von’ in their names. Those members of the family living in Frankfurt and Vienna were thus known as von Rothschild, whereas the Paris, and later the Naples, branches of the family adapted this to the French style ‘de’. In England, Nathan Mayer Rothschild eschewed ‘foreign’ titles, and is reputed to have declared that “plain Mr Rothschild” was good enough for him. A letter in the Archive from Amschel to Salomon and Nathan in November 1816 reads, “…..James and Carl received the nobility. It is a pity that Nathan did not want it.” Nathan’s sons thought differently, and in 1818 successfully applied to use the Austrian title, using the French style ‘de’ rather than the German one.

In 1822 the Rothschild brothers were awarded an Austrian Barony granted by Imperial Decree. The Barony was granted to the five brothers and their heirs and descendants of both sexes. The design for the arms was modified at this stage to include a seven-pointed coronet, and there were five arrows, the lion and unicorn as supporters, three helmets and a latin motto: ‘Concordia, Integritas, Industria’ (Harmony, Integrity, Industry).

‘Five arrows’

The five arrows became an enduring symbol of the Rothschild name. The story comes from ancient Chinese myth and also is told by Plutarch of a wealthy man who, on his deathbed, asked his sons to break a bundle of darts. When they all failed, he showed them how easily the arrows could be broken individually, cautioning them that their strength as a family lay in their unity.

Many members of the Rothschild family began to adopt the motif on letterheads, bookplates, porcelain, and jewellery. Some individuals preferred to see the arrows pointing upwards, in spite of the official description of the arrows approved by the Austrian heralds of arms. Although this was purely a matter of personal choice, a cross-channel split of opinion began to develop. The French family and bank gradually adopted ‘arrows up’ for all uses of the symbol, while the English remained faithful to the ‘arrows down’ version.

The Rothschild Archive is responsible for maintaining the family tree of the male lines of the Rothschild banking family descended from Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744-1812), and the Archive also keeps records of the female lines. Note: Rothschild was by no means a unique name and there were other (unrelated) families called Rothschild originating in Frankfurt, and other (unrelated) families have adopted the name (or versions of it) over the years.

The Rothschild Family Tree

The Rothschild family featured on this website shows the descendants through the male line of Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744-1812) of Frankfurt. The online Rothschild Family Tree is derived from The Rothschild Family Index, compiled in 2000. Go to the Rothschild Familly Tree »

The link will open in a new window. There are two ways in which you can interact with the genealogy:

- You can manually browse by clicking and dragging with your mouse to move around the area of the tree.

- You can search by typing (e.g. Nathan) into the box that appears at the top of the genealogy. Matching searching results will be returned in a list. You can then click on any of the entries and the tree will automatically move to that person.

Once at an entry on the tree, you can view more detail about that person by clicking on their box. You can then automatically traverse across to other people in the tree by clicking on their generation/position number (e.g. 3.1). This number denotes generation (top-to-bottom) and position (left-to-right) within the tree. For example, 3.1 means 3rd generation (as measured from Mayer Amschel) and 1st position chronologically within that generation.

Rothschild ancestry

The most detailed published genealogy of the Rothschild banking family is Le Sang des Rothschild by Joseph Valynseele and Henri Mars (Paris: ICC Editions, 2004). Rothschild was by no means a unique name and there were many other families called ‘Rothschild’ originating in Frankfurt and many other unrelated families bearing the name ‘Rothschild’ exist around the world.

Rothschild family biographies

For short biographies of members of the Rothschild family descended from Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744-1812) of Frankfurt, please Go to The Rothschild Family: Biographies »

The courage to dissent

Photo courtesy of Amanda Rothschild.

Given the global refugee crisis stemming from Syria’s civil war, the focus of MIT graduate student Amanda Rothschild’s work — how the United States responds to genocide — has arguably never been more relevant.

Rothschild’s dissertation, “‘Courage First:’ Dissent, Debate, and the Origins of U.S. Responsiveness to Mass Killing,” analyzes the policies of seven administrations in the face of five cases from the 20th century. The cases include the Armenian and Rwandan genocides and the atrocities in Bangladesh and Bosnia.

But the beating heart of Rothschild’s research is the Holocaust. Both of her father’s parents were survivors. Many family members perished; others were saved and went on to help others. The dissertation is dedicated to their memory.

“I’ve always been interested in issues of anti-Semitism, hatred, genocide, and mass atrocity,” Rothschild says. “Political science seemed like a great field to examine those issues because it’s interdisciplinary — it draws on history, economics, even philosophy.”

While studying the Holocaust and World War II, Rothschild was struck by the role that public servants and inner-circle influencers played in changing President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s attitude toward Jewish refugees. In 1943, whistleblowers in the U.S. State Department worked with officials in the U.S. Treasury to document practices of, among other things, disinformation and delays in processing rescue efforts — all designed to limit the immigration of Jews to the United States. Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau Jr., Roosevelt’s closest Cabinet adviser, presented the findings to the president in January 1944. The War Refugee Board was established days later.

“One of the conventional arguments related to why states don’t respond to genocide and mass killings is that they lack political will,” says Rothschild. “But I found that to be vague. My argument specifies what ‘political will’ means. It’s a complex of factors originating in domestic politics.”

After analyzing the five cases, she identified three elements required to move the needle on response to atrocities: dissent, usually at the highest levels of government; considerable Congressional pressure; and political incentive — the idea that inaction carries some political cost for the president. Because all three are needed, and because they can take years to develop, Rothschild says, “we don’t often see a prompt or robust response after a crisis emerges.”

Which is why, she adds, the Obama administration has not changed its policy on Syria — despite a State Department memo signed by 51 diplomats in June that called for military action against Bashir al-Assad’s government: “The civil servants who used the dissent channel were not in the inner circle of the president, and there seems not to be a lot of pressure from Congress or political cost to President Obama for not acting.”

Brutality and bravery

As the title of her dissertation indicates, Rothschild is particularly impressed by the courage of dissenters, especially those at lower levels. “Because they don’t have access to the president, they might use the dissent channel, risking retaliation, or resign. They’re sacrificing their own professional future and livelihood for the well being of others,” she says. “That contrasts starkly with presidents, who are primarily motivated by political considerations when they do act. There’s this interesting juxtaposition of very altruistic people and very self-interested people in the same case studies.”

While her thesis explains rather than advocates, Rothschild says, “part of my driving motivation for understanding these issues is so that we might be able to address them more effectively.” That motivation derives its urgency both from her family’s history and from her own life. In the mid 2000s, a series of anti-Semitic incidents at her high school had a “profound influence” on her career goals. To address the incidents, school administrators invited civil rights expert Frederick Lawrence, a Jewish faculty member, and Rothschild herself to speak. She considered becoming a civil rights lawyer. In the end, she opted for the “deep study of politics” over law.

Fitting in at MIT

MIT was a perfect fit for Rothschild not only because it’s a place that “cares about applying research to a big problem the globe is facing,” but also because it welcomes her historical approach. “Researching an important topic, applying that research, and being open to using the best methodologies to answer the question you’re trying to ask — it was the complete package for me,” she says.

In addition to receiving multiple awards and graduating summa cum laude from Boston College, Rothschild played Division I ice hockey there, and the athletic experience enriched her academic life: “Division I sport is very results-oriented, so you get very good at taking feedback, addressing it, and producing,” she points out. She played goalie, and the desire for her research to have an impact parallels the duty and potential intrinsic to that position. “Being a goalie, you had the ability to influence the outcome of the game. I liked that responsibility.”